TOOLS I HAVE MADE

Like most builders I know, from time to time I find a task which cannot be done easily with a tool (power or hand) which I can buy off the shelf. In that case, I often devise and make a tool of my own which will do the job. I have to admit that this is one of the real pleasures of guitar building -- it is often a significant intellectual challenge and when it works it is deeply satisfying. On this page I will collect a few of the tools I have made (or had made for me if I don't have the equipment to do it) and explain them.

First, a few words about why I do this and other more cosmic thoughts. Generally speaking, my motivation to build a special tool is to be able to perform the given task with greater accuracy and control (often the same thing). Building guitars often requires working wood to accuracy's of 1/64" or more, and repeatability is often important. While it is theoretically possible to do almost any task with only simple hand tools, it would be very difficult to have the precise control I want, and it would take an immense amount of time. At the risk of sounding trite, time is money, and it is very difficult to make money selling guitars built in this fashion. Which leads to the unintended, but very welcome consequence of building tools to perform a task with greater precision -- almost always you save a huge amount of time as well.

Another thought -- many of the ideas I have used are not original. Guitar makers are a remarkably sharing group, and I have never met one who tried to hide or protect their ideas. Probably the two makers who have given me the most ideas have been Stu Mossman (early on) ( Just a note here: Stu recently died (February, 1999), and he will be missed by many.) and Jim Olson. Stu Mossman's factory was the first I ever saw which had an appreciable amount of tooling, and it was a revelation to me. I immediately went out and bought a spindle shaper. Jim Olson and I have known each other since he first began (about 1978 if I remember correctly--I was the "old man" of guitar making in Minneapolis / St. Paul at the time) and have always delighted in "bragging" to each other about our new tools or new techniques. While Jim has probably "stolen" a few ideas from me, I know I have lifted (or modified or butchered) many from him.

In addition, there are almost always an infinite number of ways to "skin the cat." My ideas are not always (or even often) the best way. I think that the real mechanism is that seeing someone do a job with a "new" tool leads me to think about how to improve my own technique and leads to an entirely different way of doing it - inspired by someone else but still my own idea. The main thing we need, often, is simply to change our perspective -- to realize that there may be different or better ways, and take it where you personally are comfortable. And since it appears that I am beginning to lecture, I'll stop now and just show a few tools.

I bind the Peghead of most of my guitars -

with a tortoise shell binding and a wbw purfling. As the curves

on the top of both my peghead shapes are quite sharp, it is hard to hold

the pieces properly in place while the glue dries. Tape simply won't

do it, and neither will any elastic I have tried. So, I built a

small "clamp" which puts pressure exactly where I want it.

It uses small clamp screws with swivel heads (which I bought from a machinists

supply house) and is anchored in the tuner hole. It uses a carefully

shaped Plexiglas caul between the clamp screw and the peghead which evenly

distributes the pressure. It works easily and quickly. Except

for the clamp screws, which cost perhaps a dollar each, it is all hand

made and inexpensive. I have used these for several hundred guitars,

so the amortized cost per guitar is infinitesimal.

I bind the Peghead of most of my guitars -

with a tortoise shell binding and a wbw purfling. As the curves

on the top of both my peghead shapes are quite sharp, it is hard to hold

the pieces properly in place while the glue dries. Tape simply won't

do it, and neither will any elastic I have tried. So, I built a

small "clamp" which puts pressure exactly where I want it.

It uses small clamp screws with swivel heads (which I bought from a machinists

supply house) and is anchored in the tuner hole. It uses a carefully

shaped Plexiglas caul between the clamp screw and the peghead which evenly

distributes the pressure. It works easily and quickly. Except

for the clamp screws, which cost perhaps a dollar each, it is all hand

made and inexpensive. I have used these for several hundred guitars,

so the amortized cost per guitar is infinitesimal.

This

is a very low tech, but invaluable tool. I bought a steel "I"

beam at the local metal scrap yard, and took it to my friendly local

machine shop (For many years that meant literally next door) and had them

grind both flat surfaces to a true flat surface. They are wonderful

for clamping various parts together. Most obviously, I use it when

clamping fingerboards to the neck. Your imagination will suggest

a lot of other ideas.

This

is a very low tech, but invaluable tool. I bought a steel "I"

beam at the local metal scrap yard, and took it to my friendly local

machine shop (For many years that meant literally next door) and had them

grind both flat surfaces to a true flat surface. They are wonderful

for clamping various parts together. Most obviously, I use it when

clamping fingerboards to the neck. Your imagination will suggest

a lot of other ideas.

I

have recently started using vacuum

clamping for a number of tasks -- I love it. This is a fairly

"old" technique in the general woodworking industry, but the

cost was high. I first heard about using it in guitar making from

Richard Schneider, who had an article about it in the Luthier's Mercantile

catalog (if memory serves me right). In addition, Jim Olson uses

it a lot. So I bought a simple venturi style vacuum pump (it works

off compressed air from my compressor), bought a few cheap fittings and

was off to the races. The jig shown here is for slotting fingerboards.

It is made from Formica covered MDF -- a material sold for router table

tops. The top has a "ring" inset in which a closed foam

material is inset, and the "tree" pattern you see is simply

shallow groves designed to distribute the vacuum. The vacuum holds

the fingerboard firmly to the jig. You may notice two pins at the

ends--these locate the fingerboard. The bottom of the jig has slots

cut to match the scale length, and these are placed on a metal "finger".

This means I can use a single blade, (a "screw slitting blade"

-available from most machinist's supply houses) and at the cost

of a few supplies and a small amount of time, I can have a jig for

any scale length. It works very well, and costs next to nothing.

The saw itself (which I will show in a separate photo when I get around

to it) was custom made for me by a slightly crazy machinist in Wisconsin.

It works perfectly.

I

have recently started using vacuum

clamping for a number of tasks -- I love it. This is a fairly

"old" technique in the general woodworking industry, but the

cost was high. I first heard about using it in guitar making from

Richard Schneider, who had an article about it in the Luthier's Mercantile

catalog (if memory serves me right). In addition, Jim Olson uses

it a lot. So I bought a simple venturi style vacuum pump (it works

off compressed air from my compressor), bought a few cheap fittings and

was off to the races. The jig shown here is for slotting fingerboards.

It is made from Formica covered MDF -- a material sold for router table

tops. The top has a "ring" inset in which a closed foam

material is inset, and the "tree" pattern you see is simply

shallow groves designed to distribute the vacuum. The vacuum holds

the fingerboard firmly to the jig. You may notice two pins at the

ends--these locate the fingerboard. The bottom of the jig has slots

cut to match the scale length, and these are placed on a metal "finger".

This means I can use a single blade, (a "screw slitting blade"

-available from most machinist's supply houses) and at the cost

of a few supplies and a small amount of time, I can have a jig for

any scale length. It works very well, and costs next to nothing.

The saw itself (which I will show in a separate photo when I get around

to it) was custom made for me by a slightly crazy machinist in Wisconsin.

It works perfectly.

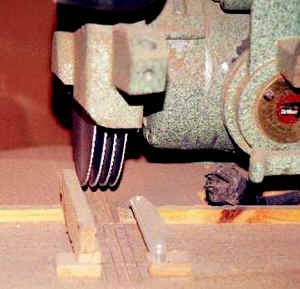

Making kerfed linings is one of those

jobs which always seemed to me should be mechanized -- I can conceive

of no possible benefit to "hand work" for this piece of the

guitar. At the same time, buying them from some of the suppliers

seems awfully expensive. Cutting the long triangular strips is relatively

easy -- it is a simple setup on my table saw, and the trick is to do several

hundred at a time so that that setup time is spread out over many guitars.

Cutting the slots evenly and accurately was more difficult, until I made

this tool. It is a very old DeWalt radial arm saw (It was my father's

and I remember when he got it in 1955!!) and I simply had spacers made

so that I could gang 4 blades at once. This makes the job

4 times as fast, and then a simple reference mark makes it possible to

move the linings forward the correct amount. The small guides you

can see are designed to help me hold 4 strips at a time, and provide a

guard to keep my fingers out of the way. Again, simple but effective.

Making kerfed linings is one of those

jobs which always seemed to me should be mechanized -- I can conceive

of no possible benefit to "hand work" for this piece of the

guitar. At the same time, buying them from some of the suppliers

seems awfully expensive. Cutting the long triangular strips is relatively

easy -- it is a simple setup on my table saw, and the trick is to do several

hundred at a time so that that setup time is spread out over many guitars.

Cutting the slots evenly and accurately was more difficult, until I made

this tool. It is a very old DeWalt radial arm saw (It was my father's

and I remember when he got it in 1955!!) and I simply had spacers made

so that I could gang 4 blades at once. This makes the job

4 times as fast, and then a simple reference mark makes it possible to

move the linings forward the correct amount. The small guides you

can see are designed to help me hold 4 strips at a time, and provide a

guard to keep my fingers out of the way. Again, simple but effective.

This

is the jig I use to cut the dovetail in

my bodies. I cut the dovetail after the end blocks are attached

to the ribs but before the top or back is attached. I use a router

with a dovetail cutter and a template follower to follow the edge of the

jig. The jig is adjustable for size, and matches the shape of the

jig for the neck dovetail.

This

is the jig I use to cut the dovetail in

my bodies. I cut the dovetail after the end blocks are attached

to the ribs but before the top or back is attached. I use a router

with a dovetail cutter and a template follower to follow the edge of the

jig. The jig is adjustable for size, and matches the shape of the

jig for the neck dovetail.

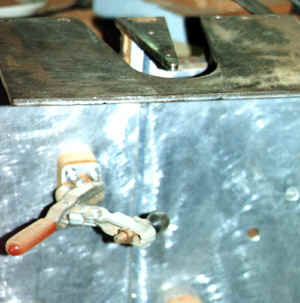

This

is the jig for cutting the dovetail

on neck blanks. Although the photo doesn't show it well, there

is an alignment piece that fits in the truss rod slot, and the De-Sta-Co

clamps hold the neck in place. The dovetail is cut with the same

dovetail cutter/template follower as is used for the body.

This

is the jig for cutting the dovetail

on neck blanks. Although the photo doesn't show it well, there

is an alignment piece that fits in the truss rod slot, and the De-Sta-Co

clamps hold the neck in place. The dovetail is cut with the same

dovetail cutter/template follower as is used for the body.

This

is really not a home built jig. Many luthiers are using a sanding

jig which is simply a piece of MDF which has been hollowed out to the

same radius as the back and back braces (in this

case, a 15 foot radius). By putting sandpaper on this, and rotating

it around on the back of the ribs, one can shape the back (and the attached

linings) to the exact profile for a perfect fit to the braces. This

is a wonderful tool. I bought the form from LMI, and my contribution

is to glue on sandpaper, and attach handles to make it easier to manipulate.

I also drilled a hole in the middle so that it can rotate around a pipe

which is placed in the middle of the ribs (I will add photos of this operation

when I next do it).

This

is really not a home built jig. Many luthiers are using a sanding

jig which is simply a piece of MDF which has been hollowed out to the

same radius as the back and back braces (in this

case, a 15 foot radius). By putting sandpaper on this, and rotating

it around on the back of the ribs, one can shape the back (and the attached

linings) to the exact profile for a perfect fit to the braces. This

is a wonderful tool. I bought the form from LMI, and my contribution

is to glue on sandpaper, and attach handles to make it easier to manipulate.

I also drilled a hole in the middle so that it can rotate around a pipe

which is placed in the middle of the ribs (I will add photos of this operation

when I next do it).

This

jig, which is made from another of the LMI forms for back radius, is set

up as a mold for gluing the back to the ribs. The foam provides

the proper resilience to make it work well.

This

jig, which is made from another of the LMI forms for back radius, is set

up as a mold for gluing the back to the ribs. The foam provides

the proper resilience to make it work well.

This

is the vacuum jig which I built for gluing

top braces. It is simply a flat work board (Which is made of more

of the router table stock) and a maple frame which has a piece of 1/16"

rubber sheeting in it. The bottom of the frame has a "ring"

of close pore foam to properly seal to the work board. A vacuum

line is then attached to the work board and the photo shows the result.

A better description of such a device is found in the LMI catalog.

To me the real advantage is that I can quickly glue a set of braces in

place, and after 5 minutes or so, open it up to remove any glue squeeze

out, after which I simply clamp it up again.

This

is the vacuum jig which I built for gluing

top braces. It is simply a flat work board (Which is made of more

of the router table stock) and a maple frame which has a piece of 1/16"

rubber sheeting in it. The bottom of the frame has a "ring"

of close pore foam to properly seal to the work board. A vacuum

line is then attached to the work board and the photo shows the result.

A better description of such a device is found in the LMI catalog.

To me the real advantage is that I can quickly glue a set of braces in

place, and after 5 minutes or so, open it up to remove any glue squeeze

out, after which I simply clamp it up again.

These are clamps we use

for repairing top cracks. (See next photo). The silver colored

clamps are commercially available (Stewart MacDonald). The big ones

we had made by a machinist friend years ago. (Having access to a machinist

-- or having those skills yourself -- is invaluable) Although not

used too often, they are invaluable when needed.

These are clamps we use

for repairing top cracks. (See next photo). The silver colored

clamps are commercially available (Stewart MacDonald). The big ones

we had made by a machinist friend years ago. (Having access to a machinist

-- or having those skills yourself -- is invaluable) Although not

used too often, they are invaluable when needed.

Clamps in use.

Clamps in use.

These tools have a special meaning for me. They were made for

me by Mike Osgar, a friend when I first opened

my shop. Mike worked for Lyon and Healey in the 1920's and moved

to Minneapolis during the depression. When I first met him he was

repairing and making instruments in his basement and garage, and did some

of the most beautiful work I have ever seen -- Mike was a true master

craftsman and was a great inspiration to me. He made these out

of old files and the handles are apple wood from a tree in his back yard.

They take and hold an incredible edge, and I treasure them. Mike

was more than a handworker -- he had devised and made some very

elaborate and beautiful tooling with which he made all the banjo bridges

for the Gibson company for many years.

These tools have a special meaning for me. They were made for

me by Mike Osgar, a friend when I first opened

my shop. Mike worked for Lyon and Healey in the 1920's and moved

to Minneapolis during the depression. When I first met him he was

repairing and making instruments in his basement and garage, and did some

of the most beautiful work I have ever seen -- Mike was a true master

craftsman and was a great inspiration to me. He made these out

of old files and the handles are apple wood from a tree in his back yard.

They take and hold an incredible edge, and I treasure them. Mike

was more than a handworker -- he had devised and made some very

elaborate and beautiful tooling with which he made all the banjo bridges

for the Gibson company for many years.

Note: Recently I received an e-mail from Mike Osgar's grandson, asking for any thoughts I had about Mike. Here is my response:

Bryan:

A delight to hear from you. I first met Mike in the early 70's when he

came to our shop just to visit. Later I visited him at his home on Minnehaha

Ave, and saw some of the work he was doing. He had grafted an extension

on a banjo neck and the work was just perfect -- both the wood working

and the touch up of the finish. After that I saw Mike quite a few times.

We would visit at his shop, or vice versa. One day Mike brought in the

chisels shown on the web site. He had made them out of old files (a very

time consuming job, since you can't let the metal get too hot while grinding)

and the handles were made from an apple tree in his back yard. One of

the things that impressed me the most was that although Mike was "old"

and very much an "old world craftsman," he was not an "old fart." The

evidence of this was to go into his shop in the garage back of the house

(completely different from the shop in the basement). He had a very elaborate

and modern setup to make banjo bridges for the Gibson Co. He made all

their banjo bridges. He had some very elaborate machinery, with highly

specialized cutters which he had made to his own specifications. Mike

and his next door neighbor, Gunnar, made the bridges.

I remember Mike as a very warm and accepting guy. I remember having lunch

at their house and afterwards his wife insisted on giving us (My partner

Rod and I) some homemade lye soap she had made. Mike was always very encouraging

to us and while I only learned a few specifics from him (I do one rather

specific thing to the bracing of my large guitars that I learned from

Mike, and have never seen anyone else do this), what I did learn from

Mike was an appreciation of old instruments and the value of careful craftsmanship

- it didn't matter if I was using a hand chisel he made or a very sophisticated

machine tool, that care was still there. A very valuable lesson. I have

very fond memories of Mike and still think of him often.

I recently got a second spindle shaper - having two has

helped a great deal, and the new one can be used as a router table as

well.

I recently got a second spindle shaper - having two has

helped a great deal, and the new one can be used as a router table as

well.

Once I got the second shaper, I rearranged part of the

basement to hold both shapers and to properly store all of my shaper jigs.

This has worked out very well.

Once I got the second shaper, I rearranged part of the

basement to hold both shapers and to properly store all of my shaper jigs.

This has worked out very well.

This website and all of its content, text and images are copyright ©1997-2011 by Charles A. Hoffman. All rights reserved.